When Stanley Hauerwas was informed that he had been named by Time magazine as one of America’s “best” theologians, he responded as he ought to have responded: “best is not a theological category.”

Similarly, the word “successful” is not a theological category. So when I say that David Congdon’s little book on Bultmann is successful, I hope I’m not making a categorical mistake.

Nevertheless, I will persist.

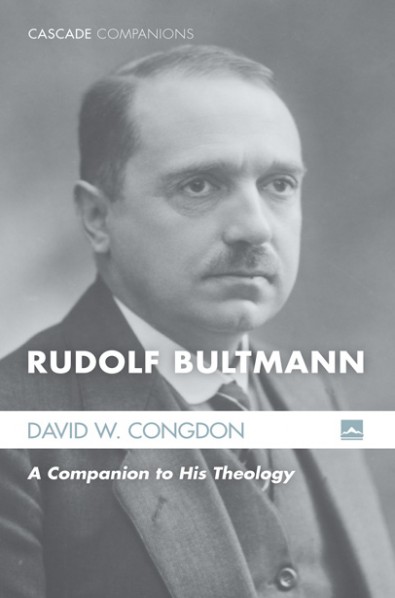

There are at least three reasons why Congdon’s book, Rudolf Bultmann: A Companion to His Theology (Cascade, 2015) should be rightly designated a “successful” theological book–successful because it gives good reason for those who have either given up, or never even looked at him in the first place, to give Bultmann a(nother) chance.

THREE REASONS TO READ CONGDON’S BOOK, or, THREE REASONS TO GIVE BULTMANN ANOTHER CHANCE

1. Congdon successfully casts into serious doubt, if not demolishes, many of the (mis)perceptions that many have held and taught about Bultmann’s thought.

I don’t know which friend it was that Congdon is speaking about who “upon finishing the famous programmatic essay on demythologizing for the first time, told me he kept waiting for the sinister demythologizing he had heard so much about but which never arrived” (xv), but I, too, had a similar experience a year or two ago after reading Jesus Christ and Mythology. Clearly, not everything I had been taught or read about Bultmann is true.

That said, let me also say that Congdon’s book will not necessarily transform readers into devoted Bultmannians.That is because defending Bultmann isn’t so much what this eminently readable book is all about–even if Congdon is clearly sympathetic to much of what Bultmann was saying. Rather, the success of Congdon’s book is that he portrays, with great clarity and with excellent primary evidence, a portrait of Bultmann not as one who was seeking to destroy faith–as some conservative critics are still apt to assume–as much as he was seeking to preserve faith in God in the increasingly secularized and scientifically-oriented modern world. Congdon helped me to realize that I need to be much more cautious in teaching others what Bultmann’s program represents.

Most important in re-orienting me to Bultmann were the three chapters respectively entitled “Eschatology” (chapter 1), “Dialectic” (chapter 2), and “Self-Understanding” (chapter 4, which in my opinion, was one of the most clarifying chapters of the whole book). For it was in these three chapters that I discovered how Bultmann was locating himself in the 20th century debate about the nature of the kingdom of God (ch. 1); was seeing himself as a faithful participant, together with the early Karl Barth, in the project of dialectical theology (ch. 2); and was seeking to show that “faith understands God only by simultaneously understanding oneself, because the God [we] encounter in revelation is the God who justifies [us]”(60 – ch. 4).

Here I have to ask: Does this latter statement not sound a whole lot like Calvin in the opening pages of his Institutes?

Our wisdom, in so far as it ought to be deemed true and solid wisdom, consists almost entirely of two parts: the knowledge of God and of ourselves. (Calvin, Institutes, I.1)

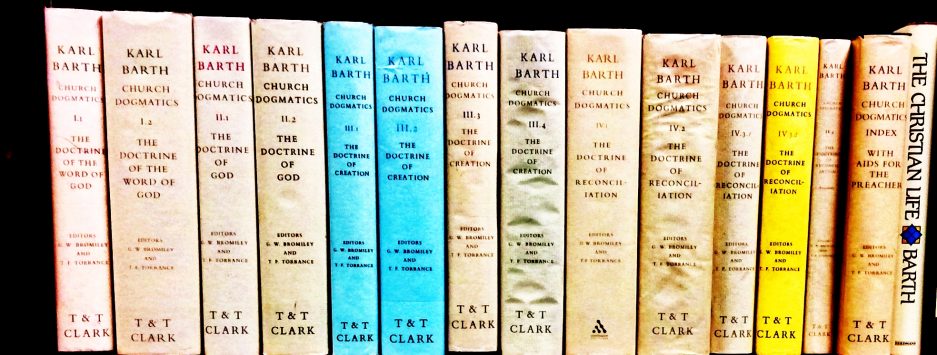

2. Congdon successfully makes the case that Bultmann should not be interpreted only through the lens of his associations and disagreements with Karl Barth.

One of the most clarifying moments I had in reading Congdon’s account was in his chapter on “dialectic” where he highlights, in line with Bruce McCormack, that it is Bultmann, not Barth, who most consistently works out the existential theology first discovered in Barth’s commentary on Romans. In other words, the true “heir” of the early dialectical theological programme inaugurated by Barth is none other than Rudolf Bultmann! As Congdon explains,

Barth would eventually change his mind [after his Romans commentary] about . . . eschatology. In his later dogmatic writings, he grounds the eschaton, and so theology, in the historical person of Jesus, and thus replaces existential theology with a certain kind of christocentric theology. Bultmann, however, consistently develops the theology of Barth’s Romans. . . . If Bultmann remains faithful to the theological position of the early Barth, then it follows that he remains a dialectical theologian, even in his later work.

In other words, in as much as the roots of dialectical theology can be traced to Barth, Bultmann is more properly the one who seeks to “conserve” these roots. Thus, when Barth later broke publicly and adamantly with Bultmann, it wasn’t because Bultmann had changed, but because Barth had changed! (If you want to get a sense of my own interpretation of Barth’s mature understanding of dialectic, take a look here.)

Of course, the question remains whether one is persuaded to follow Barth’s christocentric vs. Bultmann’s existential theological center. But after this, I will follow Congdon in pointing out that Bultmann is actually more consistent in carrying out Barth’s earliest form of dialectical theology than Barth himself. It also illustrates yet another place where there was more change in Barth than he often was willing to admit.

3. Congdon successfully demonstrates that Bultmann, whether one agrees with his approach or not, was not trying to destroy faith, but to understand faith under the conditions of modernity.

It is the case that to this day, Bultmann’s concept of “demythologization” is still commonly understood as simply seeking to” de-supernaturalize” the teaching of the Bible. Take Bultmann’s following oft-quoted statement:

We cannot use electric lights and radios, and in the event of illness, avail ourselves of modern medical and clinical means and at the same time believe in the spirit and wonder world of the New Testament. (quoted in Congdon, p. 105)

This statement has been regularly used as a key piece of evidence that Bultmann didn’t believe in miracles or that he somehow thought that everything in the Bible needed to be explained in naturalistic terms. However, as Congdon argues,

Bultmann does not think that belief in the wonder world of the NT can be isolated from the cultural context in which that belief comes to express, just as the use of the radio and modern medicine presupposes a distinct cultural context, as missionaries to remote tribes today understand well. Indeed, he would say this spirit and wonder world is not even an element of the NT kerygma, since it was a world-picture shared by everyone in that cultural context. It was as natural to them as our belief today in the capacity of scientists to discover the biological cause of a person’s illness. The early Christian apostles necessarily made use of their world-picture in bearing witness to what God had done in Jesus of Nazareth, but that can be no more essential to the kerygma than the use of Greek or Aramaic. (105-6)

So what, then, is Bultmann trying to do? Congdon convincingly argues that Bultmann was trying to take seriously the fact that we live in a “radically different–even incommensurable–cultural context from the authors of scripture, though this does not preclude intercultural communication since . . . we are not reducible to our cultural situation” (107)

Once again, we may or may not agree with how Bultmann sought to carry out what is essentially the missionary task of translating the Gospel into various 21st century contexts and cultures, but few would disagree that the task nevertheless needs to be done. Few, if any, believe that we can simply read the pages of the Bible in original Greek or Hebrew to a modern audience and expect them to hear and respond to the Gospel. Yet this is what Bultmann, Congdon argues, was simply trying to find a way of doing. In other words, Bultmann wasn’t trying to desacralize an “other-worldly” Bible into a “worldly” Bible, but was actually trying to highlight the dangers of pretending that we can bring the “other-worldliness” of the Bible into our world without risking the loss of its essential other-wordliness altogether!

Let me conclude simply by commending Congdon’s “little book on Bultmann” to you, especially if you aren’t quite ready to delve into his “big book on Bultmann” quite yet. That is my next task…!

I always appreciate when tremendous thinkers and writers are revisited, especially after they were cast in a negative light. We must constantly come back to the table as we evolve and grow and re-engage. Thanks for this post. Carl