The following is the manuscript of a presentation I did, together with my pastor and colleague, Dr. Blayne Banting (playing the part of the host, Ian McKinnen) at Briercrest College & Seminary Faculty Colloquium, April 8, 2016. I hope you enjoy it as much as I enjoyed writing and playing the part!

Interviewer (IN): Good afternoon. Welcome to “Theology Today” here on BCS radio. I’m your host, Ian McKinnen, and we are pleased to have a special guest with us today, the eminent Swiss theologian, Professor Dr. Karl Barth. Dr. Barth is professor of dogmatics at Basel University, a post held since 1935! Welcome, Dr. Barth. You are looking very well today!

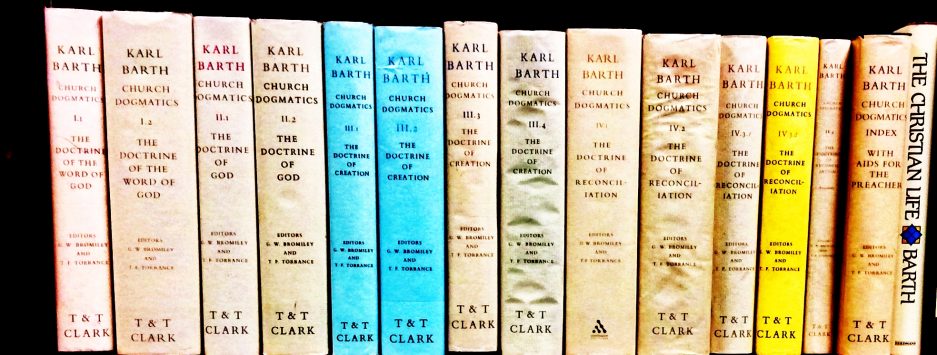

Karl Barth (KB): Guten Tag, Herr McKinnen! I blush at your comment of my appearance. I had difficulty with my hair this morning. But please, call me Karl! If I were speaking Deutsche, I would be glad to address you in the familiar du! And I am sehr happy to share some time with you, even though I must admit that it was difficult to pause in the writing of my Church Dogmatics this morning. You see, I am working on a troubling section entitled the “sloth of man” and not long ago I finished a section called the “pride of man.” When I received your kind invitation to come on the show today, I pondered the extent to which I am subject to the judgment of both categories: Pride, for agreeing to be interviewed in such an auspicious setting, and sloth, for delaying work on my Church Dogmatics!

IN: Well, then, I guess we are fortunate that we were able to appeal to your pride to convince you to be on the program! I hope God will show you a measure of grace for choosing the program over your dogmatics today!

Now, as you know, our objective this morning is to get a handle on the essential character of your life-long work in theology. Here in the English speaking world we have become accustomed to speaking of your work, along with others such as your colleagues Rudolf Bultmann, Paul Tillich, and Emil Brunner, as “neo-orthodox theology.” Can you comment on this broad theological characterization?

KB: Neo-orthodoxy! It is such an unfortunate and distasteful term, wouldn’t you say? It is of first importance to understand that while I have sufficient reserve of Christian charity to acknowledge Bultmann, Tillich, and Brunner as co-laborers in the task of dogmatics, I continue to be dismayed that I am lumped together with them as colleagues under this rather crass and misleading category called “neo-orthodox theology”! Indeed, those who call me neo-orthodox are just about (though not quite) as single-mindedly concerned to paint me into the corner of their predetermined categories as those American fundamentalists who denounce me even while seeking to open conversation with me. You can understand, I hope, that I have little patience for such simplistic caricatures.

Nevertheless, I am honour bound to address your question formally. First, it should be of interest to you that virtually no Deutsche speakers in Europe, not even my harshest opponents, have adopted the term “neo-orthodox” except you Anglophones, especially those in America. More substantially, I reject the term “neo-orthodox” as an appropriate descriptor because of its unfortunate inference that somehow my theology represents a “new orthodoxy.” As if it were my task, or even those of my dogmatic colleagues, to provide the Church with a new orthodoxy! That has never been my goal or vocation, nor should it be the goal of any theologian or preacher—even if it appears to me that Tillich and Bultmann have in some ways capitulated to this felt need to find new ways of addressing modern man in his present theological existence!

No, on the contrary, I see my task as a theologian to be a servant to the Church by assessing and clarifying its proclamation of the Good News against the standard of God’s own self-revelation in the person of Jesus Christ. Indeed, this is not only my task, but the task which every generation of the Church is called upon to do.

IN: So if I am to understand you correctly—and if I wish to maintain a good friendship with you in the future!—I should herewith refrain from calling you a neo-orthodox theologian!

KB: That would warm my heart greatly! And even more so if I knew that my critics would at the very least allow me to reject their labels, even while I allow them perfect freedom as theologians to reject my conclusions! But to be utterly clear for hopefully the last time, let me simply say that I am at least as far from neo-orthodoxy as I am today from my old desk now residing at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary! (Imagine that—they wanted my desk, which of course, I joyfully gave up in exchange of a new-fangled model now in my home in Basel! I now feel like a Swiss banker sitting behind that grand piece of furniture! Dear old Luther didn’t know the half of it when he spoke of the mirifica mommutatio, the wonderful exchange!)

IN: I’m more than a little envious! I wish someone would allow me to trade in my old desk for a newer model! At any rate, you’ve made your non-neo-orthodoxy stance eminently clear. Nevertheless, before we fully leave this topic behind, might I ask the question from a slightly different angle? If you reject the designation of being a “neo-orthodox” theologian, is it true that, at the very least, you are seeking to be “orthodox” in your theology?

KB: That is a much better question, Ian. Of course, there are a few theologians who would proudly plant their flag against orthodoxy. (Though I have my suspicions about certain theologians whom I will not name!). So, yes, for what it’s worth, I am one with Christian theologians throughout history who see themselves working on the side of orthodoxy.

However, note this well: I am deeply concerned that the concept of “orthodoxy” has become a mere conceptualization or even historical descriptor dissociated from the reality of God himself. My dear old teacher, Herr Professor von Harnack, fondly identified orthodoxy as if it were some kind of latter political consensus isolated from the Gospel and Jesus himself. In contradistinction from him, however, I understand orthodoxy, not as an independent conceptual rule of faith standing outside or historically beyond the canon of Holy Scripture, but a characteristic which can only properly be associated with God himself. There is, in a very real sense, only one who can be orthodox, and that is God himself in his own self-speaking. Materially, orthodoxy can only be spoken of strictly as the content of God’s own self-disclosure of his eternal existence in the person of Jesus Christ. Thus, even the biblical authors are themselves witnesses to orthodoxy and are restricted, at the very least, by their own human finitude. Here the saying, finitum non capaxi infiniti—the finite cannot contain the infinite, is appropriate. Consequently, all human doctrinal statements, whether creeds, dogmatics, or even the Scriptures themselves, are what they are relative to how well or how poorly they witness to the orthodoxy that can be said of only God himself.

IN: Dr. Barth, your discussion of orthodoxy has led me to an increased state of cognitive dissonance. Do you see yourself working for orthodoxy or not? If God alone can be truly “orthodox” in his speaking, what might that say about your own theological programme and conclusions?

KB: If it is possible to resist a question while welcoming the questioner, that is where I find myself at this moment. For you see, I do not accept the assumption I believe is embedded within your question. If, by asking of my orthodoxy, questioners want to know how well my theology aligns with the particular historical forms of the Church’s proclamation—whether that form be that of the Apostles’ or Nicene Creed, the Westminster Catechism, or even the Barmen Declaration of which I played a central role—well, I refuse to use those forms to be the measure of my own theology’s “orthodoxy.” I view these documents, as wonderful as they are, as the formal witnesses of the Church to the material reality of God revealed personally in Jesus Christ. Thus, when I say I am on the side of orthodoxy, it is because I count myself to be a theologian of witness to God’s very own Word, Jesus Christ. It is not so much that I aim to pass a test of orthodoxy against this historic statements and dogmatic proposals, as much as I hope that my statements and dogmatic proposals will serve as signposts to the living Orthodoxy of God himself, the right worship of God (orthodoxy, after all, means “right worship”) initiated, incarnated, and consummate by God himself as Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

And so, to be short—and you know dear Ian that I have long struggled to speak about most matters with brevity!—the only standard of orthodoxy is the living rule which, or more properly, who is God’s own Word, Jesus Christ, attested to in Holy Scripture and proclaimed in the Church.

IN: That is intriguing! But now I am left with a conundrum, Dr. Barth. The purpose of our interview was to try to get at the essential character of your theology. So if we cannot pin your theology down as either neo-orthodox or orthodox, it still begs the question, then, how we shall characterize your theology? So, I suppose this is a good point to transition to the main substance of what I wanted to talk with you about today.

I know that many have designated your theology a “theology of crisis,” while still others have called it “dialectical theology.” If you are neither happy with orthodoxy or neo-orthodoxy as descriptors, what about these concepts? For us English speakers, at least, the idea of a theology of crisis sound very much like a theology responding to an emergency. Is that an accurate way to describe what you have been attempting?

KB: Ahh, the theology of crisis! This designation brings back a flood of memories from my days spent in Safenwil while I was a pastor and when my friend Eduard Thurneysen and I would converse late into the night on the discoveries we were making! We called it learning our theological ABC all over again from the beginning. As I reflect on those heady early days—you will remember that it was right around the time of the Great War—that there was indeed a sense that Thurneysen and I were seeking a theology in response to an emergency. The urgency we felt was that so many of the German intellectuals under which we had just finished our theological studies were now standing up publicly to justify the war effort by making it seem as if God were obviously and unreservedly on their side. Despite my utter respect for my teachers such as Harnack and Hermann, I became increasingly dissatisfied— alarmed even—with the confusion which their pronouncements were causing.

IN: What kind of confusion and distinction are you talking about?

KB: If I were to make it as plain as possible, it seemed to me then—and now!—that an important distinction was being lost between the words of God and the words of us, mere men. You see, the reality of the world as God sees and describes it and the reality of the world as we see and describe it are qualitatively and infinitely distinct, to play on a phrase of dear old Søren Kierkegaard. Indeed, there is an even greater distinction between God’s perspective on the world and ours than between the perspective of Kierkegaard and a Great Dane, though the Philosopher and the Canine are both great indeed!

IN: I hadn’t taken you as either a lover of existentialist philosophy or of large dogs! But I will be transparent here and confess that I’m struggling to understand what you are talking about, despite your clever metaphor. Can you unpack this a bit more? Surely you mean more than simply the declaration that God’s words and man’s words are simply different?

KB: Ha! Don’t feel badly, dear Ian. I lead a sheltered life and I realize that my metaphors, not least my jokes, are strained, at best, and often simply bad, at worst!

I think the best way to clarify is to return to the observation you made earlier about how the word “crisis” in English is used quite differently than the way I, and even those who were naming the early theological movement of which I was a part, were using it. As you noted, for English speakers “crisis” speaks of an emergency which must be dealt with in the moment, but which, once sufficiently attended to, ceases to be a crisis. But for me, the meaning of the word “crisis” arose out of my study of St. Paul’s Epistle the Romans. There I discerned that the whole world, due to not only to its sin, but its finitude, was under the judgment, the word krisis in Greek, of God. Thus, the crisis, the judgment, under which we and the world persist, is, according to the apostle, that God’s judgments alone are right (Romans 2:5), and ours are insufficient. God alone is capable of speaking rightly about what the world is like and indeed, what we are like. Conversely, whatever we might say about God and the world constantly comes under his judgment. It is in that sense, then, that those observing my work from close and from afar came to speak of my theology as a theology of crisis, a theology which resisted—Protested!—the assumption that we could be confident of the correspondence between our words and the reality of God. God, in other words, did not simply rubber stamp the word “Yes” across each of our theological pronouncements either on him or the world. On the contrary, we first needed to come under the same weight of judgment under which Paul labored, mainly, that all us men are all under God’s Judgment of “No” all of the time and against all of our clever theological words.

IN: Ahh! Now I see why some the early observers of your work suggested that your commentary on the Epistle to the Romans fell like a bombshell on the playground of the theologians! While so many others were saying, “If God be for us, who can be against us?” you were saying, “Let God be true and every man a liar!” (Rom 3:4).

KB: You are a quick study, my dear Ian! If you had just submitted that comment on a theological examination, I would be pleased to give you a bonus point!

IN: Ok. Here is another question that will perhaps give us even sharper insight. I recall an early essay of yours in which you mention the strange world of the Bible. Does this have anything to do with the theology of crisis?

KB: Yes! You are right to recall that essay of mine. You see, it was while I studied the great Epistle of Romans I rediscovered the “strange world in the Bible” you mention. I called it strange because the world portrayed in Holy Scripture speaks of a cosmos created, ruled, and held accountable to God and to God alone. Contrast that with our modern era, with our mighty ships, war machines, and banking empires (and believe me, we Swiss know a thing or two about banking!) which seems to portray a world created, ruled, and make accountable us mere men. But herein lies the clash: Between the world of reality—the essentially alien world in which God is Creator, King and Judge over all things, and the essentially comfortable world of illusion which we daily inhabit—the world of our social, economic, political, and philosophical construction. The former world, the world over which God is Lord, seems to us moderns to be a fairy tale and myth, while the latter, the world in which we find ourselves daily laboring in at our homes, businesses, schools, and government, seems to us to be “really real.” But according to God’s own Word, this latter world is not only an illusion, but a delusion. Consequently, for us to hear God’s Word—to really hear it!—is to first hear that all of our perceptions of what is real, and good, and right, is countered—nein, contradicted! —by God’s righteous judgment. In that sense, the hearing of God’s Word to us, today and every day, is the unsettling experience of hearing that our highest cultural, intellectual, and even aesthetic achievements (with perhaps some room for exception in the music of Mozart!) falls short of God’s Word and God’s glory!

IN: Although I understand now what you are saying, I have to confess: It is quite unsettling to me, and perhaps to our listeners, if what you say is true. It sounds to me like you are claiming that all of our judgments as humans can never quite “cut the mustard,” as the colloquialism might put it, and that whatever we say and do, God already speaks in contradiction to us. Is that correct?

KB: Fortunately for you, you are correct to understand the situation as I have put it in that way, but unfortunately for all of us, you are also correct in your assessment! As you yourself quoted, “Let God be true and every man a liar!” (Rom 3:4) Let me simply say that the crisis, the judgment, under which we find ourselves before God is not temporary—a crisis in your English sense of the word—but a permanent situation under which we find ourselves as creatures, even before we fell into sin. Even in the biblical creation account before the fall, God alone is God and we are dust. It just so happens that the situation in which we find ourselves as rebellious sinners after the Fall simply puts us at a two-fold distance from God—a distance first inherent in our creatureliness and now second, exacerbated in our sinfulness.

IN: This is unsettling indeed. But we must now move on! Now, I had spoken to you that I wanted to speak to you about the notion of your theology being “dialectical” in nature, and in speaking of it in that way, I assumed that “dialectic” meant something along the lines of “dialogue.” But if we are in what I might call this “metaphysical contradiction” between God and us humans—how can we speak of theology as dialectical, or dialogical? Is there any sense in which your understanding of theology as a “dialectical” task has anything to do with the common understanding of dialectic as dialogue?

KB: Let me assure you, friend, that your understanding of dialectic is not far off the mark. The word “dialectic” has many senses, but you are correct that in its most basic sense, dialectic is dialogue or conversation. Thus, theology, as a human task, is in fact an exercise in dialogue. It is, after all, a dialogue amongst human conversation partners much as we are doing today. But if that were all there was to theology—a cluster of clever or not so-clever individuals engaged in conversation about supposedly divine matters—then theology would be no different than any other human conversation, whether in philosophy, grammar, history, art, or even science. No, what makes theology a unique kind of dialogue is because its primary dialogue partner is not simply other humans, but God himself! We speak because God has first spoken. As I said from the early days of my first attempt at dogmatics while in Göttingen, Deus dixit, “God has spoken and continues to speak.” This, my dear friend, is the fundamental assumption which theology must make if it is truly to have God as a conversation partner, and not to be simply talk about God amongst us men. If God has not first spoken, then all our speaking is circular and speculative. It may be interesting, even poetic, but there is no guarantee whatsoever that it could be true or fruitful. True dialectical theology is thus nothing less than the response of prayer and praise to God.

IN: Dr Barth, I am unsure to what extent you are familiar with some of the classic films in America, but at this point, I am beginning to feel a bit like Westley and Buttercup in The Princess Bride as they faced the Fire Swamp! It feels like we are facing an insurmountable challenge forward or backward! If I may, please let me try to put these two concepts together: On the one hand, you seem to be saying that the reality of the utter and infinite qualitative distinction between God and humans makes the possibility of saying anything meaningful about God, well, impossible. And yet on the other hand, you are saying that theology is a dialogue, a conversation of sorts between God and humans, albeit a conversation initiated by God. Are we not in a contradictory or at least paradoxical situation in such a state of affairs? If you will forgive my infelicity, it sounds like you are speaking out of two sides of your mouth by telling us that theology is impossible, on the one hand, and yet insisting on its possibility, on the other!

KB: An impossible possibility, you say? I am drawn to the beauty of that phrase such that I may use that phrase myself some day! But yes indeed, you catch the essence of what it means for theology to be dialectical in nature.

Perhaps it would be helpful for me to point you to another essay of mine where I unpacked this “impossible possibility” situation (see, I am already plagiarizing you!) as following: “As ministers we ought to speak of God. We are human, however, and so we cannot speak of God. We ought therefore to recognize both our obligation and our inability and by that very recognition give God the glory.” You see, my eloquent examiner, I believe most strongly that our words can never, in and of themselves, capture the very essence and nature of God as he is. So in that regard, you are right: It is impossible to speak of God. But that said, the Scriptures demand of us, the Church, nevertheless to be witnesses to God’s action in Christ. “You will be my witnesses” (Acts 1:8), Dr. Luke records Jesus saying. And so, though we cannot speak of God, we nevertheless must, even while acknowledging the extremely constrained limits of our human language. Consequently, there is only one more thing we can do in such a difficult situation, and that is to pray that God would take our words, commandeer them even, to use them by his mercy and grace, to testify of himself, to the praise of his glory.

IN: The dialectical way of looking at the task of theology is compelling. Nevertheless, as I listen to you on this, I have cause, obviously, to wonder if there are alternative ways to look at the task of theology. Are you suggesting that this dialectical method of yours, if I may be so bold to call it a method, is the only and correct way to do think about and do theology?

KB: Such a very good question, Herr McKinnen! I should very much enjoy having you in one of my seminars at Basel to liven the bunch up on occasion! Indeed, you are right to wonder about other ways of thinking about the task of theology. In fact, the history of Christian dogmatics reveals at least two other non-dialectical ways of thinking about theology’s task. I call these two the way of dogmatism and the way of self-criticism respectively.

In dogmatism, the theologian seeks to speak very directly, by way of the Bible and by way of the settled dogmas of Christianity (Christology, Trinity, etc.) about who God is and what he has and is doing. Indeed, I acknowledge that this is the historic way of so-called “orthodoxy” which seeks to conserve the longstanding teachings and assertions of the faith by reiterating what has already been said and tested in the past to be in congruence with Holy Scripture. As the ancient theologians were apt to view it, theology has nothing to do with declaring the novel or new, but only with re-affirming the ancient and true. In the way of dogmatism, the words of the Churches in its creeds, dogmas, doctrines, confessions and even its hymns are assumed to have the capacity to capture, at least in approximation, the reality and truth of God. This is the way which medieval and Reformed scholastics understood the task of theology, and which, in my moments of deep introspection, I am drawn to myself. Here I freely confess that it is the theologians of the dogmatic method from whom I learned much of God and his ways.

However, the other way, the way of self-criticism, or better, the way of self-judgment or negation, represents the venerable mystical tradition of Christian theology—the via negativa. Here the theologian explicitly and implicitly knows that all of his or her statements about God simply are wholly inadequate. Consequently, the way of mysticism is when, in the end, the human confesses that God is fundamentally the One who he or she desires but who is otherwise fully unknowable—ineffable, unable to be named—and who is not him or herself. At best the theologian can utter the negative, albeit utterly true, maxim that God is not us!

But in the end, my dear Ian, I remain convinced that the dialectical method is the preferred “third” option. And this is not because I can prove it to be superior, but because I believe it better corresponds to the fundamental assumption I see evident in Paul and the Bible writ large, mainly, that there is an infinite qualitative disjunction that exists between God and creation. God as the Lord is eternally “over against” the world and never to be confused with the world. But God is also the one revealed in Scripture to be the one who is Immanuel, God with us, and who has, by his own self-disclosure in Jesus Christ, allows himself to be known by us as we seek him in faith. As I see it, we humans are compelled to speak dialectically because we stand simultaneously affirmed and negated, negated and affirmed, by God himself.

IN: I see that I have some homework cut out for me to catch up with these developments, but I also see from our producer that we are running out of time, Dr. Barth—Karl! Thus, to wrap up our conversation today, may I ask this: As you think of this important concept of dialectic theology, what would you most like our listeners to remember?

KB: To return where we started: The theologian, the pastor, the everyday Christian, is called upon to speak about and of God, but we simply can’t do so due to the finiteness and fallenness of our humanity. This is the real dialectic that exists in the fullness of divine and created reality when considered together. Nevertheless, in obedience to God’s call, Christians (and indeed, all peoples whether Christian or not) are designated to be witnesses to God’s saving acts in Christ and so therefore we are obligated to speak. Christians, thus, in greater and lesser obedience to the call, must therefore speak. This is the dialectical method by which we seek to do theology, indeed mission and evangelism and preaching and pastoral care, a method which I believe more closely corresponds to the dialectical reality that exists between God and the world. This method simultaneously allows God alone to be God (which the way of self-criticism aptly asserts), but also allows the possibility of human language to be used by God’s Holy Spirit to say something meaningful and true about God (which the way of dogmatism is confident can happen). Thus, dialectic keeps both divine and human poles of speech active without allowing either the Godness of God to be confused with human language, or the humanness of language to be confused with God’s own speech. In this way, theology is a confession of our weakness before an Almighty God, and yet also a prayer of hopefulness in a gracious and good God who deigns to be with us in our weakness.

IN: At this point, I wonder if our listeners are, with me, feeling weak in the knees as we consider how to live up to the demands which this dialectical theology seems to impose!

KB: I have and do feel some of the anguish you are experiencing, Mr. McKinnen. So let me comfort you with this: Being weak in the knees is the entirely appropriate response because it demonstrates, hopefully, that it is not our words or theological concepts that justify or save us, but only God’s own speaking and God’s own initiative by his grace that ultimately matter. Weak-kneed people can only fall to their knees, together with the publican, and plead with God that he would be merciful to us sinners. It is then and only then we may cry out “Soli Deo Gloria! To God be the glory alone!”

IN: Thank you, Dr. Barth. You have given us much to ponder!

KB: Thank you, Herr McKinnen! Please come and visit my home in Basel some day!