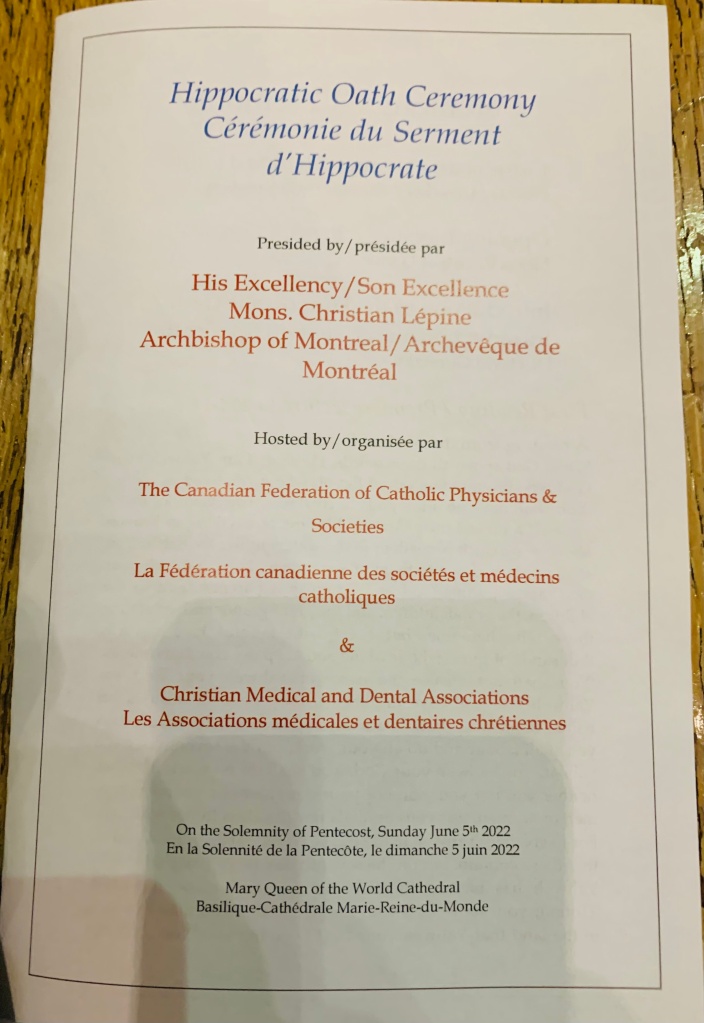

The following was a talk I gave in Montreal, Quebec on June 5, 2022 at a ceremony where physicians present and online were able to affirm or re-affirm the Hippocratic Oath.

Hippocratic Oath Ceremony – Montreal – June 5, 2022 – David Guretzki, PhD

Good evening. I want to thank the Christian Medical & Dental Association for taking the initiative to put on this wonderful event. I feel deeply honoured for being asked to play a small part. In this regard, I send my official greetings to all of you here and online tonight from the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada. The EFC is an association of 45 denominations, 33 post-secondary institutions, and over 70 Christian organizations, all representing over 7000 evangelical congregations across Canada. So, on behalf of the EFC and its affiliates, let me be the first to thank those affirming the Hippocratic oath this evening. I hope that you hear my expression of gratitude not only from the EFC, but from the hundreds and thousands of patients whom you have and will care for in the future. By publicly affirming the oath, you commit not only to professionalism and care, but you demonstrate your conviction that all human life, from conception to natural death, is sacred and that all humans, created in God’s image, are honoured by God and thus need to be honoured and protected. We have deep respect for all those who choose to promote life over death, who choose to walk difficult paths with and to serve those who suffer. We honour and thank you for this commitment, a commitment that God only knows is likely increasingly bound to create professional and personal challenges for you. Nevertheless, may I say with all the confidence of the promises that Holy Writ provides: God is with you and will not forsake those who walk in the paths of life and righteousness. Though humans and their laws and policies may fail, our Creator God will not.

In the few minutes that I have with you today, I want to comment on why I believe committing or re-committing to the Hippocratic oath is so vital in the times in which we find ourselves. Let me speak to our context, to our convictions, and finally to the comfort of those of us on the receiving end of a medical professional’s care.

First, taking the Hippocratic oath should be seen in our cultural context as a counter-cultural protest. In 1995 Pope John Paul II brought attention to what he called the growing “culture of death” in which abortion and euthanasia were increasingly prevalent. As he put it, “Choices once unanimously considered criminal and rejected by the common moral sense are gradually becoming socially acceptable.” One can only imagine the horror with which John Paul II would recoil if he knew how far Western society had gone nearly 30 years later not only in making abortion and euthanasia socially acceptable, but legally protected and liberally promoted.

It is in our current cultural context that public affirmations for the protection of life become increasingly strategic and spiritually significant. It is one thing for religious institutions such as the Catholic and Evangelical churches to affirm the need to protect life. May we continue to do so. But it is another for those working within the health care system to risk personal and professional censure and discipline to affirm their commitment to refuse to participate in life-ending procedures such as abortion and euthanasia. In this regard, we should all view this ceremony tonight not only as meaningful to the individual oath takers and their families—which I am sure it is—but also as politically and socially significant to the broader public which needs to hear that there are still those who have not and will not cave in to legal, professional, and cultural pressures to go along with the death culture.

It is interesting that in the past several years, public protest has become a regular feature of the news cycle. Protest is now commonly seen as something done in the streets before parliaments, legislatures, and courts. While there is and should be a place for peaceful protest in our land, we shouldn’t underestimate how a simple act of reciting the Hippocratic oath, from the heart and with solidarity together as a group, is a form of non-violent protest. To recite the Oath is not only a matter of personal conviction and conscience. It is also a small but real spiritual, political and cultural challenge to the principalities and powers, as Scripture calls them, the visible and invisible forces that drive our political and cultural movements. It is a necessary reminder that not all approve of human manufactured methods of death. Not all equate the intentional ending of human life as mere expression of personal autonomy or choice. And so, as you recite the oath, and as we listen, may we all be attuned to the very corporate, spiritual, and political protest that even this ceremony is.

Second, let me speak to the matter of conviction. Even though the Oath has changed over the millennia, a couple fundamental convictions undergird the Oath and remain consistent. The first is that the Oath bears witness to the recognition that a physicians’ accountability, while certainly including friends, family, teachers and indeed, professional associations and guidelines, is fundamentally to something, or properly Someone, above and beyond all these. It is notable that the provenance of the original Hippocratic Oath pre-dates the Christian era. The original oath was sworn in the presence of the gods and goddess of the pantheon, and versions since have modified the oath to contextualize it to the theological and religious culture of those affirming it. The version today will be affirmed in the presence of The Almighty. Presumably, most here will mentally translate “The Almighty” to mean the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the God who most fully reveals his name to be Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Of course, as a Protestant theologian, I have no ecclesiastical authority to place my imprimatur on such a conceptual translation for the phrase “The Almighty”—I will leave such possibilities to Archbishop Lépine if he so wishes!—I can nevertheless fully endorse a Trinitarian interpretation here today! It is in the name of Father, Son and Holy Spirit in which this oath is being uttered today and it is this conviction which underlies and empowers the affirmation itself.

But even for non-Trinitarians who affirm the oath, the ancient version of the Hippocratic oath testifies that the morality and practice of medicine is subject to a transcendent reality beyond human government, legislation, or even Physicians’ Guilds. The conviction that human life needs to be protected, preserved, and sustained as humanly and practically as possible derives not from the genius of human mind or even some kind of moral evolution of the human spirit, but is derived from a reality without, indeed, a reality from above. The Oath in this regard has long symbolized the conviction that the axioms and practice of medicine itself is authorized by a reality above and pre-dating all human institutions, the State and Professional Colleges included. The Oath testifies to a divinely-given conviction, in other words, that humans are not the measure of all things, as one Greek philosopher wrongly asserted. On the contrary, we recite the Oath out of the conviction that ultimately, as Jewish and Christian Scripture alike affirm, that one day we will all give an account before God the Almighty Judge in whose image we are created and commanded to reflect.

Second, the oath continues from even its original version unambiguously to affirm the conviction that a physician ought to refuse to engage in life-ending practices of euthanasia and abortion. As the original oath intones, “I will not give a lethal drug to anyone if I am asked, nor will I advise such a plan; and similarly I will not give a woman a pessary to cause an abortion.” Of course, I am well aware that some newer versions of the Oath have edited these axiomatic lines out, but we can all be heartened that the brave souls here today reciting the oath have not shrunk from reciting lines substantially in agreement with the ancient words. With this I, and I hope we, believe the invisible presence of God and his holy ones, rejoice.

Finally, let me speak to the matter of comfort that comes from witnessing these physicians recite the oath. Here I speak not of a cheapened version of comfort that has become prevalent today—the narcissistic comfort of knowing that I am in control of the date and manner of my own death and that physicians will stand ready to ensure this can happen. On the contrary, I speak to the comfort of the many ill, disabled, poor and disadvantaged souls these days who are becoming increasingly confused about their relationship to their physicians and health care providers. Are these professionals with whom we’ve entrusted our very physical bodies concerned ultimately for our good and of our life? Or are we to be fearful that one day, the same practitioner who today healed and nursed me back to health might tomorrow turn her or his hand against me and take my life?

The fact that this group of people here and across the country stand ready to recite this Oath is not only as a public witness and outworking of a set of fundamental theological or religious convictions, but as a tangible means of giving comfort to all of us who one day, too, will walk in the valley of the shadow of death. Today, more than ever, patients and families need reassurance that their physicians, surgeons, nurses, and palliative specialists, are committed to practicing their medical art, as the oath says, “with purity, holiness, and beneficence.” People must be assured beyond a shadow of doubt that their medical caregivers are there for “the benefit of patient,” which is implicitly defined in the oath as having “the utmost respect for every human life.” Knowing their physician is there with that same “utmost respect for life” provides the greatest comfort desired to those who seek aid and help in their physical need, both when the need is small and curable but also when their need is terminal and without cure. Such is the crying need for an army of Physician-Comforters who need not ask whether today their marching orders are to protect life or, horrifically, to end life.

Let me conclude by saying that I am deeply moved and heartened to see the people here who are on the cusp of affirming or reaffirming their commitment to beneficent medicine, medicine practiced against the dominant streams of culture, medicine practiced in view of the transcendent reality of our Creator God, medicine practiced now and always to honour the sanctity, the sacredness, the holiness of the gift of life which our Father, Son and Holy Spirit has given to us as a trust. May you, your families, your colleagues, and all your patients and their families be divinely blessed by the outworking of the oath you recite today. Thank you.

Now interestingly, of his total life, Enoch is accounted with 300 years of faithfulness to God, which, incidentally, began at the age of 65 after he had fathered Methuselah. (Methuselah, you will recall, is the one who is credited as having the longest human life in the Bible—or ever!—of 969 years).

Now interestingly, of his total life, Enoch is accounted with 300 years of faithfulness to God, which, incidentally, began at the age of 65 after he had fathered Methuselah. (Methuselah, you will recall, is the one who is credited as having the longest human life in the Bible—or ever!—of 969 years).