With Christmas just around the corner, here’s “three points” which Karl Barth emphasized about Christmas, and which I think those who have Christmas preaching responsibilities to fulfill will do well, like Mary, to ponder deeply in our hearts in preparation for the Christmas sermon.

1) The inclusion of Bethlehem, Caesar Augustus, and Quirinius in the Christmas narrative reminds us that this not a myth, a legend, or fairy tale, nor even a morality tale of “peace and goodwill to all men.” Indeed, the real “meaning” of Christmas is missed if it is preached in order to evoke a general feeling of humanitarian goodwill to the less fortunate in society of whom we dutifully are reminded year after year. On the contrary, the story of Christmas, with its specific historical referents (Bethlehem, Quirinius, etc.),

signifies that when the Bible gives an account of revelation it means to narrate history, i.e., not to tell of a relation between God and man that exists generally in every time and place and that is always in process, but to tell of an event that takes place there and only there, then and only then, between God and certain very specific men.

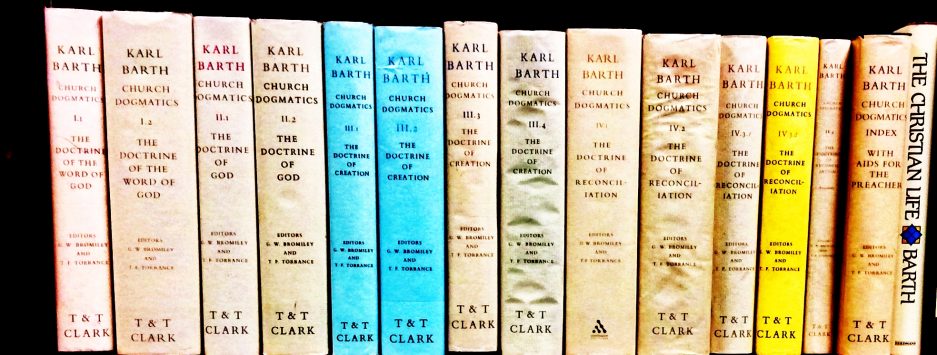

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, I/1, 326.

In other words, Christmas preaching has little to do with the morality of peace and goodwill, but has everything to do with God’s good will of appearing in Jesus of Nazareth in the midst of our human history to bring us peace with him. Christmas isn’t a churchly Aesop’s fable extolling humility, peace, and general goodwill, but an astounding recollection of the unparalleled and mysterious in-breaking of God into the world! Consequently, preachers need to be wary of proclaiming the Nativity as if it were a lovely children’s story that highlights shepherds and donkeys and managers which gives hearers a warm, fuzzy nostalgic feeling about their childhood Christmases when the world seemed more peaceful and quiet than it really was. Rather, preachers must boldly tell the story in such a way as to heighten its significance for what it is: an unexpected intrusion into the status quo of our everyday lives–lives lived almost entirely on the safe predictability of cause and effect. The Christmas story is not yet proclaimed as Gospel if it only draws us back into the memory of “Christmases past” instead of leading us into the unknown future life of Christian discipleship, where it is the unexpected things of God which shatter the comforts of everyday religious routine, yet which is really the origin of true peace, shalom, with God and with our fellow human being.

2) Not only is Christmas a mystery of God with us, it is a miracle of God with us. True, Christmas is a time to announce the coming of God to us in Jesus at a specific time and place to specific people (and therefore to be proclaimed in historical terms), but Christmas is also the time to announce an utterly “new event” (a novum) unlike any other event and understood as something transcending historical understanding. Indeed, Christmas is, in the first instance, to be understood in light of Barth’s basic understanding of a miracle: as something which occurs in history, but which cannot be understood as arising from or having its origin in the normal course of historical events. In the section entitled, “The Miracle of Christmas,” Barth describes revelation (and therefore, the event of Christmas) as something which

comes to us as a Novum [“new thing”] which, when it becomes an object for us, we cannot incorporate in the series of our other objects, cannot compare with them, cannot deduce from their context, cannot regard as analogous with them. It comes to us as a datum with no point of connexion with any other previous datum. It becomes the object of our knowledge by its own power and not by ours. … In this bit of knowing we are not the masters but the mastered.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, I/2, 172.

Barth regularly connects the “mystery and miracle of Christmas” with the doctrine of the Virgin Birth (CD I/2, pp. 173ff.) because it is in the Virgin birth that we come face to face with a miracle–something that comes to us in the normal course of our history (“Virgin birth“) but also as something which cannot be incorporated into our history in the normal or expected way (“Virgin birth”). As he says, the Virgin birth is the doctrine which the Church posted “on guard…at the door of the mystery of Christmas” (CD I/2, 181) and which, if rushed past, most certainly leads us to miss its utterly miraculous character. Indeed, to seek to explain away the Virgin Birth is to fail to receive Christmas both as a mystery and as a miracle. On the contrary, the Virgin Birth “can be properly understood…only as a sign wrought by God himself, and by God Himself solely and directly, the sign of the freedom and immediacy, the mystery of His action, as a preliminary sign of the coming of His Kingdom.” (CD I/2, 181)

Christmas preaching, then, affirms the miracle of Jesus’ birth from the Virgin, not as a means of protecting him from the historical transmission of sin (this never seems to be the concern of the biblical authors, though this is how the doctrine has very often traditionally functioned), but as an affirmation and sign that Jesus comes to us both as God with us (i.e., as a man in the normal course of history) and as God with us (i.e., as a surprising personal presence outside of the normal course of history).

3) “The message of Christmas already includes within itself the message of Good Friday.” (CD II/2, 122.) The Christmas story, while already the Gospel of God’s coming, is only the first in a series of events in God’s self-giving revelation and salvation. The Christmas story, while fully Gospel, is not yet the full Gospel. Rather, Christmas is prototypical of the whole act of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. For in Christmas, we first find out, again surprisingly, that God’s arrival with us is in a spiritually personal presence: in Jesus of Nazareth by the power of the Holy Spirit. That is, Christmas is but the first historical lesson repeated also in Jesus’ baptism, temptation, transfiguration, death, resurrection, ascension, Pentecost, and someday, the final parousia. For in the full life of Jesus, we see over and over again that the coming of God is always personally in Jesus and spiritually in the Holy Spirit.

Of the incarnation of the Word of God we may truly say both that in the conception of Jesus by the Holy Spirit and His birth of the Virgin Mary it was a completed and perfect fact, yet also that it was continually worked out in His whole existence and is not therefore exhausted in any sense in the special event of Christmas with which it began. The truth conveyed by the first conception is that the formation and ordering of the flesh in the flesh is represented in the New Testament as a procedure which unfolded itself as it did with a necessity originally imposed upon Jesus. “I have meat to eat that ye know not of .… My meat is to do the will of him that sent me, and to finish his work” (Jn. 4:32f.). “Wist ye not that I must be about my Father’s business?” (Lk. 2:49). He must work the works of Him that sent Him, while it is day (Jn. 9:4). He must be lifted up from the earth (Jn. 3:14; 12:34). He must go to Jerusalem, to suffer many things, and be killed, and rise again, as the Synoptic predictions of the passion repeatedly say. This is the necessity of His action given at the beginning in the person of Jesus—the incarnation as an already completed fact. (CD III/2, 337)

Christmas preachers, then, must be careful to ensure that Christmas is not presented as a self-contained story that stands merely as an introduction to the Jesus’ life, after which it can be left behind as ancient history. Rather, the Christmas story, while the particular history of a particular “new man,” is a theologically pregnant story which is repeated again and again in the life of Jesus, and which continues to be repeated again and again by analogy in every new man or woman who enters Christ’s body by the conception of the Holy Spirit. Christmas, in other words, is the true prototype of every new beginning, of every new creation in Christ Jesus. Christmas tells us that because of that day when God became flesh, today is always a new day in which the cause/effect of the decaying sinful history of man born into sin under Adam is abruptly broken into through the new birth of the Holy Spirit who leads us into union with Christ, the second (but really, first) Adam.

The Word of grace tells us . . . [that] the future has already begun, not an empty future still to be fashioned, but a future already filled and fashioned in a definite way, the future of the man who lives here and now just as the old past was his past, the future into which he here and now has the freedom, capacity and power to enter as his own most proper future. This future has begun with the fact that God has fulfilled His covenant with man, that He has loved the world and reconciled it with Himself, that He has introduced the justified and sanctified man as the second Adam (who was before the first). . . .The new man is born. It is worth noting that our Christmas carols tell us this in every possible key. If only our Christmas preaching would bestir itself no less distinctly to say the same! Since the enslaved man who was can be no longer, all that is needed is that he should now be the man he is.

Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, III/1, 246.

Fantastic post David. Thanks.

awesome post. thanks. Happy Advent as you wait for his coming!

Loved your insights!