I will always remember with fondness the German theologian Helmut Thielicke’s (pronounced, “tea’-lick-ah”) little classic entitled, A Little Exercise for Young Theologians. On the opening page, Thielicke explains, “I must see and hear my listeners not only as students but also as souls entrusted to me.” (p. 1)

As I reflected on this, I was reminded once again, as I begin my 17th (!) year of teaching in a theological college and seminary, that those people who sit in my classes are not only students, but souls entrusted to me. As I thought about this, I wondered, “What might I be able to offer to my students at this particular time of year–when everything is fresh and exciting?” Although it may have been done before, I offer here my own version of the 10 Commandments for Theological Students.

1) You shall have no other god before God. I cannot bring myself to alter the substance of this first commandment. As Karl Barth put it in a famous article in 1933, the first commandment is in fact the first axiom of all theology. In other words, theological students must never forget that God is the central object of our study in theology. As important as Scripture, tradition, history, and ancient texts are, in the end, theological study that forgets that theology is about God has lost its way already. In short, the first commandment for theological study is to remember that God is a Subject who freely gives himself in Jesus Christ as an object of our study and reflection, but that a proper response must be finally one of worship–worship before the Incomprehensible, Immeasureable Holy One who cannot be captured in our words, sentences, and theological papers, and yet who condescends to be known by sinning humans. We dare not forget this most important of all axioms: The focus of study for theological students is–God. Yes, theological students will face the demands of long hours of poring over the biblical text, memorizing Greek conjugations, deciphering the difference between enhypostasis and anhypostasis, and learning how to do exegesis, homiletics, and administration. But a theological student should never forget that all of this is for naught if theology is not ultimately concerned about–God.

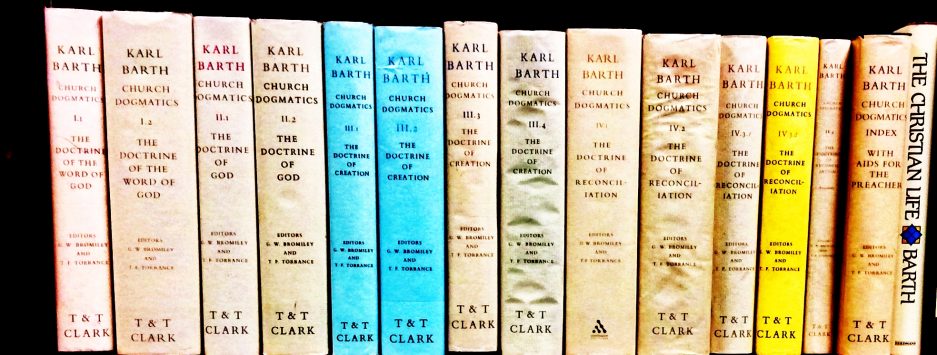

2) You shall not create a theological idol. Anyone who engages in formal theological study for any amount of time realizes that one’s preferences for some authors, scholars, theologians, or exegetes tend to narrow significantly over time. This is, at least in part, the practical reality of the theological disciplines: No one can master or read the work of everyone even within a narrow sub-discipline. Consequently, we tend to have our favorites. Now, you’ve either been under a rock, or you simply don’t know me all that well if you haven’t figured out that my favourite theologian is Karl Barth. Yours might be N.T. Wright or John Calvin or Augustine or Walter Brueggeman. The point is, beware of allowing that favourite to become a theological “pin up”–an idol, to use the biblical parlance.

True, I have no problem confessing my great admiration for the work of Karl Barth, and I read him more than any other theologian. But I also have learned that the best way to avoid idolizing a theologian is to read the opponents as well. For all my disagreements with Brunner, for example, I think that at several crucial points he had things more clearly thought out than Barth. And that helps me to remember that for all his genius, Karl Barth, too, was a sinner and was, like us all, prone to error.

But most importantly, see commandment #1 above: theological study must finally be about God, not about Barth or NT Wright, or John Zizioulos, however thankful I am for these faithful scholars. Unfortunately, it is the case that sometimes theological students become “experts” on theologians and scholars and consequently miss the main point of all theological study: to know God and his benefits, and to proclaim him to others, like us, in need of his grace.

3) You shall not take the name of other sub-disciplines in vain. It is almost inevitable that theological students will eventually assume that their chosen sub-discipline (whether systematic theology, historical theology, biblical exegesis, pastoral theology, church history, ethics, liturgics, or some other sub-discipline) is in some way superior to all others. At such points, it can be easy for theological students to become contemptuous toward students in other disciplines; but this should not be so. For in the end, the compendium of theological disciplines is analogous to the Body of Christ: Every member ultimately needs the other, even if we might secretly think that some parts are more honorable than others. Theologians need exegetes, and exegetes need historians, and historians need ethicists, and ethicists need homileticians. Rather than peering/sneering down our noses at those in other disciplines and scorning their work, I would encourage you to learn to discipline yourself to read at least one book in a discipline not your own for every ten that you read in your own. You might be surprised that they have something to teach you!

4) Remember to put to rest–temporarily–your critical theological skills while worshipping. Even though the object of inquiry in theological study is ultimately none other than God himself (see Commandment #1), theological students must learn the discipline of worshipping God while temporarily suspending their newly emerging theological critical skills. This is especially important when the sermon is being delivered Sunday morning. Though you might see all your pastor’s exegetical fallacies, call into question his intertextual references, and be puzzled by the lack of good homiletical structure in his sermon, you must learn to temporarily put to rest your critical acuities, and try to remember that like everyone else gathed together in the Lord’s House on the Lord’s Day, the Person on display is God in Jesus Christ, not the pastor or the worship leader or the Sunday school teacher. You have, after all, come to worship God and to hear from him, not to assign a grade. Of course, your training will inevitably train you to see theological problems. That is a good thing. But remember that God has appointed pastors and teachers to have spiritual charge over us, and theological discipline includes the ability to learn from even imperfect preachers. Because after all, you may well be one of those imperfect pastors and teachers yourself someday as well.

Oh, and while I’m at it: Remember the exhortation from Hebrews 10:25: “Let us not give up meeting together, as some are in the habit of doing, but let us encourage one another—and all the more as you see the Day approaching.” For some reason, theological students can be easily deceived into thinking, “I study Scripture and think about God all week long. I don’t need to be involved in a local body of believers on Sunday as well.” This is simply wrong, and I encourage you to resist the temptation to be a “Bedside Baptist” during the course of your theological study. If anything, regular involvement in a local church keeps our feet grounded in the community where the theologically educated are most needed. If there is a suspicion amongst the rank and file church goers of our day about formal theological education, it may in part be because of how often theological students account for so many of the empty spots in the pews on Sunday morning. The logic may be flawed, but it is hard to avoid the connection that so often, theological students are the least likely to be in Church, so therefore, theological education must be bad. Don’t contribute to that flawed logic. Be in Church next Sunday!

5) Honour your theological fathers and mothers. At one level, theological students simply need to learn to respect and honour the wisdom of their professors, even at times when it sounds like they might seem to be completely off-base and, indeed, theologically suspect in comparison with one’s pastor or mentor back home. Don’t get me wrong here: I’m not saying that theological professors are perfect–by no means. I know too many of them myself, and I happen to see one in the mirror every morning when I shave! But beyond honouring your teachers (they, after all, have typically committed something like 8 or 12 years after high school of study to prepare for their role) be sure also to honour your theological fathers and mothers back home as well. It can be an awful show of disrespect, after a year or two of theological education, to begin to look down one’s nose at those pastors and elders back home who may not have had the same privileges you have had, and to begin to judge them harshly for their lack of theological and biblical sophistication. In such cases, never forget that it these same “simple” pastors and teachers and elders and parents back home who are truly your spiritual fathers and mothers. It is far too easy to become a theological critic; it is far more difficult (and the sign of theological maturity) to be able to appreciate and still learn from those from whom you may have already passed in theological sophistication!

6) You shall not verbally, intellectually, or rhetorically murder your theological opponent. For the most part, theological students seem to manage to avoid physically killing one another in the heat of a theological debate. (Although in the history of Christianity, there have been some exceptions!) But my experience tells me that almost all of us (including me) will not hesitate to pull out all the stops in the heat of a theological argument. We will use every resource at hand to squash (“metaphorically murder”) our opponents. It is during those intense moments of theological debate (which, by the way, I happen to think can be very healthy) that one needs constantly to check oneself to make sure that it is the truth that one is after, and not simply the desire to win the argument at all costs. To paraphrase the Apostle, “If I decimate my theological opponent in the pursuit of truth, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or clanging symbol.” (Cf. 1 Cor 13:1) Unfortunately, in 17 years of theological education, I have more than once seen Christian fellowship broken over what really amounted to either a trivial, or unwinnable theological argument. This isn’t to commend avoiding theological arguments at all costs: Indeed, we probably need more theological debate these days than less! But always remember that ultimately, the goal of a theological argument should be more often irenical than polemical: It is for the building up of the Body, not the utter destruction of our theological detractors.

7) Do your utmost to say out of bed with the “spirit of the age.” In 1 Tim 4:1, Paul warns, “the Spirit clearly says that in later times some will abandon the faith and follow deceiving spirits and things taught by demons.” This is one of those commandments that is of uttermost importance to heed, but so easy to fall into breaking. Just as we live in an age where we are bombarded daily in the media with images and suggestions to follow our base sexual desires, so, too, theological students enter a realm where daily (or at least more often than the average layperson) there is a temptation to chase after the latest theological, philosophical, or cultural fads–all in the name of being “theologically relevant” or “up to date” or “theologically sophisticated.” Of course, it is not always easy to sort out which ideas are truly “things taught by demons” from “the truth of the Spirit.” Subtlety is, of course, one of Satan’s own tools of deception. Most of us are not caught off guard by the obviously false things, but all of us are, from time to time, tempted to get into bed with the spirit of the age, and to commit theological adultery.

So how do we avoid this falling into this temptation? Well, at one level, this is what theological education is all about–learning to discern truth from error, and to use Scripture properly to make those judgements. But in the end, keeping commandment #6 means, at least in part, learning whom to trust, and that means listening to the wisdom of teachers whom you know have demonstrated a consistent walk with the Lord, and from whom you can also learn. Oh, and pray a lot, too! As the ancients used to say, “Lex orandi, lex credendi” [The Law of Prayer is the Law of Belief].

8 ) You shall not steal time from others which is rightfully theirs. You might have thought that the eighth commandment for the theological student might be a good place to mention something about plagiarism. As all students quickly learn, it is an academic sin, whether in Christian or secular settings, to steal ideas from others and to call them your own. That’s a good thing to remember. So don’t plagiarize.

But I think that far too often, theological students can easily end up stealing something other than just others’ ideas. What? Their time. Speaking from personal and painful experience, I did two theological degrees while married, and I can without any pride at all confess that sometimes, my theological work simply was an excuse to steal time from my wife–time that really was rightfully hers, but which I justified as being not as important as time spend studying theology. Fortunately, I have an awesome and forgiving wife who has taught me much (though I am still learning) about what it really means to give of one’s time for someone else. Practically, this means that even though you are doing something really, really important (I can’t think of many more things more important in life than to set aside a portion of one’s life in focused study of Scripture and of the knowledge of God), being a theological student does not give you license to steal time from your spouse or family. If you are married, it is better to end up as a “B” student with a strong marriage, than an “A” student and divorced. In short, be prepared to resist the temptation at times to steal time from your loved ones, even though the studies you are engaged in are all about God. Here I think of Malachi’s lament:

Another thing you do: You flood the LORD’s altar with tears. You weep and wail because he no longer pays attention to your offerings or accepts them with pleasure from your hands. You ask, “Why?” It is because the LORD is acting as the witness between you and the wife of your youth, because you have broken faith with her, though she is your partner, the wife of your marriage covenant. (Mal. 2:13-14)

We may think we are pleasuring God with our wonderful theological papers and argument, and I want to affirm that indeed, God is pleased with such offerings when offered in faith. But such offerings can quickly become a stench in God’s nostrils when we break faith with our spouses in order to produce them. It is then that, fearfully, the Lord will act as a witness against us. Lord, help us!

9) You shall not misrepresent your opponent’s theological position. We all have theological opponents, and we seem to get more of them the more we engage in theological study. But theological students must learn the very difficult discipline of speaking and writing truthfully of the position of those with whom we disagree. The problem is that the opponents we most want to debunk are likely guilty of breaking this commandment themselves. The reason we are so adamantly opposed to them is because they have misrepresented us, or our favourite theologians or authors, in some way. So the temptation is to fight fire with fire. Rather than carefully showing where our opponents are indeed right on some accounts, and wrong in others, we have a built-in carnal desire to present their work as something reprehensible and utterly false. Philosopher’s call this “constructing a straw man.” Theologically, it simply is called “lying” or “bearing false witness.” While theoretically, it may in fact be possible that there are utter liars and heretics writing and teaching out there, those aren’t usually the one’s that concern us the most. Indeed, it is the ones who have elements of truth in what they are saying that we can be the most tempted to label and libel. On the contrary, the sign of theological maturity is the ability to concede and acknowledge the truth of parts of our opponents’ arguments, even while patiently recounting why the other parts of their argument are faulty. Unfortunately, such an approach takes great patience, lots of time, and a great deal of Spirit-enabled love–something that most of us are in all too short supply.

10) You shall not covet someone else’s library. I may be speaking only from personal experience here, but I suspect that a common temptation, especially among theological students, is to surpass your neighbor’s library, either in quantity (“I have more commentaries on John’s Gospel than George”) or at least in quality (“Henry may have a lot of books, but most of it is fluff! I only buy books of enduring value”). This isn’t to say that you ought not to buy books. In fact, I have a hard time understanding how some students (and even pastors) are proud of the fact that they have so few books! Books are, after all, the tools of the trade for those seeking to be engaged in the ministry of the Word. But those same necessary tools can so easily become a snare and a trap. We see our neighbor’s library shelf, or the latest theology text, or yet another book on Barth (guilty!) and we think we need to have it. Let’s face it, folks: This is the sin of coveteousness more often than we may care to admit.

So what am I commending here? I’m not saying stop buying books, but I am saying, get in the habit of counting to at least 10 (or 20 or 30!) before plunking down the cash for yet another book. I speak here of one who is guilty of having many too many books on my shelf that I have not yet read! Or better yet, see if you can borrow the book from a library instead of buying it. If after reading it you still think you need it, fine–go ahead and buy it if you can. But don’t get trapped into buying books for the sake of buying books. Take this from one who has been learning this lesson the hard way over the past years!